Dr. Michael Oberschneider counsels hundreds of local families about it every year. It’s not a new phenomenon, but understanding its dynamics is an evolving science – especially when trying to resolve problems children develop as they grow up.

Dr. Michael Oberschneider counsels hundreds of local families about it every year. It’s not a new phenomenon, but understanding its dynamics is an evolving science – especially when trying to resolve problems children develop as they grow up.

What is it?

It’s technology, and its growing use – in some cases to the point of addiction to virtual reality – by children and their well-meaning parents as a substitute for family and social interaction, and what Oberschneider calls unstructured creative play.

“Dr. Mike”, as he is affectionately known by many in Loudoun and throughout the Washington metropolitan area, is highly regarded for the work of his practice, Ashburn Psychological and Psychiatric Services. He may be even better known for his commitment to causes that help parents, children and adults cope with stress, depression, addiction and a variety of related mental health issues. Oberschneider has been featured on CNN and Good Morning America, and was recognized as “Top Therapist” by Washingtonian Magazine for his work with children and adolescents. Most recently, he was named chief mental health advisor of Loudoun’s Easy Street, LLC, which provides help to individuals with Asperger’s Disorder or High Functioning Autism.

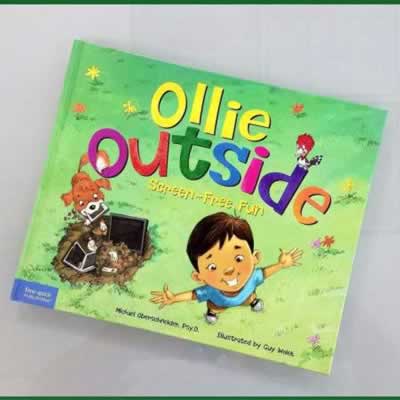

Obershneider’s new book, Ollie Outside: Screen-Free Fun, is at once simple and breathtaking in its approach and message. Written for children ages three through eight, and for their parents and caregivers, it takes the reader past the obvious notion that sometimes electronic devices ought to be turned off.

The Tribune met with Oberschneider this week for a wide-ranging conversation about the book, the issues it raises, and his work in the community.

“I didn’t write it to make money,” Oberschneider made clear right away, though he would like to see the book distributed nationwide. “I wrote it because this is a growing issue I see in my practice, and because I’ve learned what works and what doesn’t.” His comments are punctuated with evidence from empirical studies that support what he has captured in the book.

“Ollie Outside is not the story of one boy and his parents, but rather a combination of what I’ve learned over the years. It’s many stories woven into one,” he said. When asked why it was written for the particular age group, he talked about preventing problems before they become significant in a teenager’s life. The video game addicted 17-year-old, who doesn’t want to socialize face-to-face, is likely to be a more formidable case for Oberschneider and others like him than the four-year-old whose parents sit her in front of all forms of electronics erroneously believing this will contribute to her cognitive development and success in school.

“It’s just not true,” Oberschneider said when asked if early exposure to lots of technology and information is helpful later in life. He asserts that studies show just the opposite, and that attention deficit and other disorders may be more likely because children get less balance in their lives than they ought to. In particular, less exposure to the outside word, literally and figuratively. The three to eight age group is the ideal time to get on front of many developmental issues and help kids do better in life, Oberschneider said.

In his presentations on the topic, Oberschneider cites research showing that 91 percent of children between the ages of two and 17 play video games, a figure that’s even higher among just teenagers, with many more boys having access to a game console or playing games on a mobile device than girls. He agrees that video games can have positive influences, but only in moderation and not when nudity, sex, drug use, prostitution or graphic violence are involved.

He also cites statistics showing children ages five to 16 spending an average of 6.5 hours a day in front of a screen, a 117 percent increase since 1995. Teenage boys and girls each spend about the same time, an average of 8 and 7.5 hours a day, respectively, and that number has more than doubled for girls since 1995.

Limiting the use of electronics may appear counter-intuitive to parents who focus narrowly on the educational benefits of technology. And for most, answering the question of what to do instead – and why – may be even less intuitive. That’s Oberschneider’s other big reason for writing the book.

Through words and illustrations, Ollie Outside tells the story of a young boy who wants to build a fort in his backyard. He plays outside and asks for help but little is forthcoming, so he completes the fort on his own and names it “Fort Lonely.” His parents come around to understanding what’s missing — due to their own fixation with electronics and spending time indoors — and join him in the fort for dinner with the pledge “no screens allowed.” By story’s end, Ollie is surrounded by smiling parents and others at the renamed “Fort Fun.”

The choice of the word “outside” in the title is not accidental, and has literal and metaphorical implications. “Children ought to have time outside every day when practical for sun, fresh air, and interaction with others and the outside environment,” Oberschneider said. When asked if there a larger meaning to outside, he nodded his head in agreement. Outside implies something outward looking, beyond the inward focus of a hand-held device, computer or game that is typically a solitary indoor interaction with a virtual world.

Social interaction is critical to good mental health, and interaction with parents and other family members is a big part of this, Oberschneider said. Parents should not simply be trying to offset their child’s time in a world of virtual reality. Oberschneider’s case is that parents should be active participants in those real world interactions so these become part of an expected, welcome and positive norm for the child.

It’s been shown that even something as simple as children having dinner with their parents at least three times a week is better for their mental health than if they rarely eat with their parents, Oberschneider said. “It’s not the eating part, it’s the fact that everyone in the family stops to take time to talk and interact on a regular basis.”

Ollie Outside concludes with several pages of tips for parents and caregivers, all of which go to the message of the book.

Screen-free guidelines include the following:

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) now says children under the age of two should avoid screen time. Studies show that the brain of a child age two or younger isn’t developmentally able to process information from screens; young children may quickly become confused or overstimulated. Previous AAP guidance was issued prior to the first generation iPad and the explosion of apps aimed at young children. The more TV children watch before the age of three, the more likely they will experience attention problems by the time they enter school.

- Children over age two should be limited to one to two hours of screen time each day, with a focus on high-quality educational material.

- Avoid media that’s face-paced, aggressive or over-stimulating, and always avoid violent content.

- Don’t let your child use more than one electronic device at a time. This kind of multitasking isn’t good for brain development.

The book also highlights benefits of outdoor activity:

- Playing outside helps children stay active and fit. The Centers for Disease Control recommends that children do at least 60 minutes of physical activity daily.

- Children with ADHD or autism improve their concentration and focus after being or exercising outside.

- Active play promotes emotional development by relieving stress, increasing endorphin levels, and boosting mood.

- Time outside is linked to positive attitudes and kindness. Just five minutes of “green exercise” (exercising in nature) can improve mood and self-esteem at any age.

Ollie Outside: Screen-Free Fun, written by Dr. Michael Oberschneider, Ps.D., and illustrated by Guy Wolek, is published by Free Spirit Publishing and available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other sources. The “Ask Dr. Mike” column is a regular feature of The Loudoun Tribune.